International consortium undertakes groundbreaking research to identify cause of mysterious “Potato Taste” in Rwandan Specialty Coffee

A network of researchers spanning from the United States to France to Rwanda has found common cause in working to solve a grave agricultural challenge facing Rwanda. In the tiny African country, around 90% of the population works in agriculture, and coffee constitutes almost a quarter of all agricultural exports. Spurred by government and international investments, Rwanda’s specialty coffee industry emerged in the wake of the 1994 genocide. However, a mysterious “potato taste” defect, which sometimes causes coffee to taste like potatoes, now threatens the industry. The cause of the defect, which has historically baffled researchers, may occur through damage from the “Antestia bug.” Half a year into this transcontinental research partnership, experts in chemistry, plant pathology, entomology, and the social sciences have achieved impressive gains in determining the cause of potato taste. This network believes it can be the first to solve this agricultural mystery and design solutions to eliminate the defect, improving the lives and profits of Rwandan farmers.

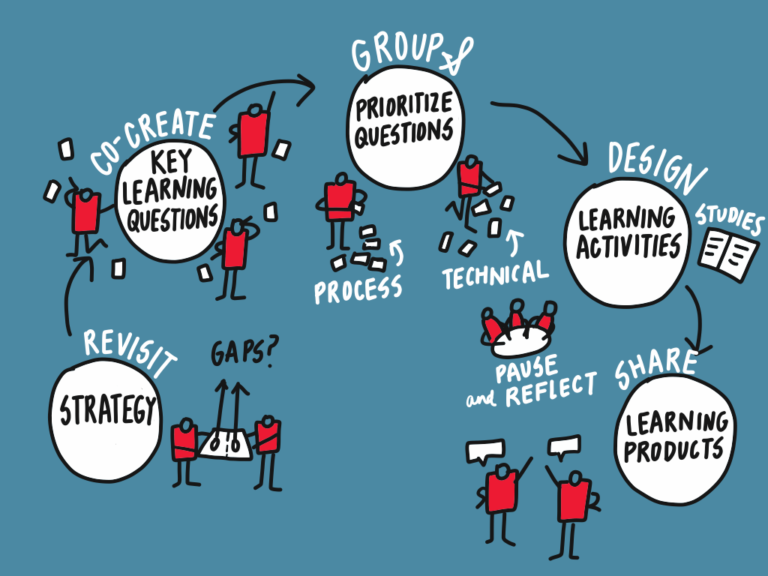

In January 2012 an international research team including representatives of the University of California, Riverside (UCR); CIRAD in France; the National University of Rwanda; and the non-profit organization The Global Knowledge Initiative convened in Rwanda to design research strategies, optimize partnerships, and leverage available resources to eliminate the potato taste defect from Rwandan specialty coffee. Following two weeks of network design and strategy, and validation from government, community organizations, researchers, and coffee companies, team members returned home and got to work. Since this meeting, the ambitious consortium has been working on multiple fronts to solve the potato taste mystery. In Rwanda, Rogers Family Company’s Mario Serracin works closely with the Rwanda Agricultural Board, Starbucks Coffee, and local Rwandan companies such as Horizon Sopyrwa to raise antestia bugs for analysis and analyze green coffee beans for evidence of potato taste. In the US, David Rider of North Dakota State University analyzes and identifies antestia samples. Thomas Miller at UCR has shipped and set up weather monitoring stations in Rwanda to monitor humidity, rainfall, and other variables to aid in determining ecological conditions favorable to antestia bugs. Miller also serves as a focal point for designing research, disseminating information about this challenge, and recruiting partners.

Susan and Charles Jackels, at Seattle University and University of Washington, Bothel, respectively, run tests on green coffee beans sent by partners in Rwanda to investigate how potato taste manifests itself chemically in coffee beans. Their preliminary research suggests stunning differences between beans with and without potato taste. In France, Christian Cilas at CIRAD, one of the first scholars to study potato taste in the early 1990s, works with France’s Pasteur Institute to unearth evidence from CIRAD’s 1990s work in Burundi and to determine potato taste’s chemical footprint. Cilas will present findings at from this work at the Association for Science and Information on Coffee Conference in Costa Rica, November 2012.

A number of factors motivate this diverse, international network—brought together and facilitated by the Global Knowledge Initiative through its LINK (Learning and Innovation Network for Knowledge and Solutions) program—to eliminate this defect in Rwandan and Burundian coffee. First, scientific intrigue drives their interests. This challenge is truly complex and mysterious. Second, the impact that solving this challenge is likely to have on smallholder farmers in Rwanda and Burundi also motivates participants. “Eliminating the potato taste defect in Rwandan and Burundian coffee will not only safeguard the reputation of Rwanda’s superlative coffee and relieve the headaches of coffee companies exporting Rwandan coffee,” notes the Global Knowledge Initiative’s Andrew Gerard, “It will also substantially improve the lives of thousands, perhaps tens of thousands of poor Rwandan farmers.”