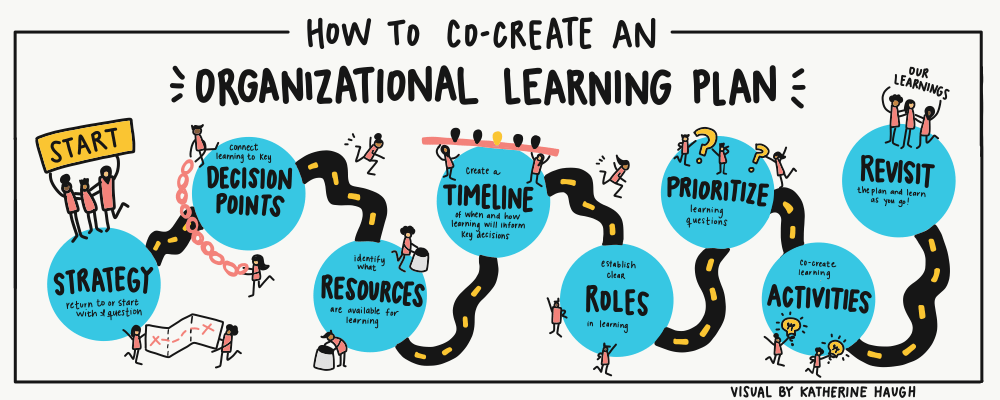

How to Co-Create an Organizational Learning Plan

This blog was co-authored by Global Knowledge Initiative’s Katherine Haugh and Social Impact’s Monalisa Salib, with credit to many thought partners along the way (see the full credits at the end of this blog.) This is the second article in a three-part series. Read part one here, and look for part 3 to be released on May 11.

As learning professionals, we get asked a lot about organizational learning plans. There is a lack of good resources out there on how to create them, including publicly available examples. This blog is part two in a three-part series and focuses on how to actually create an organizational learning plan.

In part one, we covered what an organizational learning plan is and why your organization needs one. In part three, to be released on May 11, we will talk about how to actually implement the plan for learning and adapting in your organization.

What is the minimum viable product for an organization’s learning plan?

In our previous blog about what an organizational learning plan is, we suggest that teams start with a minimum viable product, implement it, and adapt it based on what they learn. But what does a minimum viable product for your organization look like?

If your organization is just starting out on its learning journey, consider a focused plan that hones in on something that is critical to your organization. For example, focus on one way in which your organization is piloting a new approach to something. Answer these basic questions about the activity:

- What do we need to know in order to be effective and enlightened?

- How will we create, acquire, analyze, share, and use our knowledge?

- Who will do what to ensure we create, acquire, analyze, share, and use our knowledge?

- How will we resource and reinforce these practices within our organization?

Don’t think about having a learning plan that covers all your learning needs. You are just starting and want to make sure you can operationalize learning. You can start small and expand from there. (As an aside: if you are running a pilot and don’t have a plan in place for learning from it, just cancel the pilot. The purpose of the pilot is to learn and if you don’t have a plan to learn, you are missing the point. If by the end of the pilot, you have no evidence that the approach worked or didn’t, you might as well have never done the pilot.)

How do you co-create a learning plan with your team? Who should be involved in the process?

Any decent and new organizational learning plan is going to require behavior change on the part of the staff (read more about the interpersonal competencies needed on teams to facilitate organizational learning). Inputting together an organization learning plan, you must consider:

- What about ourselves must we change to implement this plan?

- What incentives or disincentives are in place for us to do so?

- What should we do about that?

It is critical to co-create the learning plan with the individuals who will be responsible for learning and adapting on your team (read: everyone) because if you don’t, you are not bringing anyone along for the ride. Team members are more likely to take ownership of learning if they participate in creating a learning plan.

When actually co-creating the plan, people will come up with amazing ideas. Make sure you ask during those ideation sessions: are we really going to do this (particularly when it requires significant change to how people interact, spend their time, etc.)? If you’re not honest at this moment with yourselves, you’ll be disappointed later. Challenge people, check in with people, and ask, “is this question strategically important?” or “what added value will this bring?” No one wants to write a brilliant, but entirely unimplementable, plan.

You may be wondering, what should you do if there are crickets (meaning silence in the room)? One potential solution is to switch up your facilitation approach — move from a large group to paired discussion. People are then forced to talk to each other, and also have a way to hear back from the pair. This will change the room from crickets to songbirds.

While it is important that your broader team is involved in co-creating the learning plan (otherwise it will be much less likely to be used), it is also important to be conscious of consensus fatigue and the different roles to be played. Ideally, everyone on the team is involved in the plan — especially validating it, (not everyone will be able to author or shepherd it through). To shepherd it, you will need someone who has a lot of social capital and can “champion” the plan — this should be a team member with significant support and involvement from leadership.

Ok, so what are the steps you can take to actually create the plan?

These steps are not always in a clear linear sequence as outlined below. You will likely need to jump back and forth between steps to create the most useful plan possible.

Step 1: Return to or start with your organizational (or team) strategy.

If you are asked to create an organizational learning plan for your team, ask first: do we have an organizational strategy? If not, suggest that you start by creating an organizational strategy. If you already have an organizational strategy, start there. Gather as a group and talk through your organization’s theory of change. What are you trying to accomplish? By when? How will you get there? Why do you think the activities you’ve chosen will help you achieve your goals? (Note: if you work for a large-scale organization like the United Nations, it is possible that you may need to spend some time with your team breaking down a high-level theory of change or create a new one that is specific to your work at lower levels.) It is important to be very challenging in this phase. Challenge your own assumptions and vocalize your questions.

When you don’t start from the organization or team’s strategy (one that is hopefully co-created with staff and stakeholders rather than drafted in a back room to motivate staff learning efforts), you will likely end up with a learning plan full of things that are nice to know rather than things that you need to know. This happens because once unleashed, people’s curiosity can take over. During future steps, people might start saying things like, “I’ve always wondered…” If you hear that, be constructively suspicious. If they’ve always wondered but never done anything about that wondering, it might be a case of the “nice to know.” Harnessing curiosity is absolutely essential, wonderful, and the lifeblood of an organizational learning culture, but too much of a good thing can leave you stretched and feeling less than strategic in your learning efforts.

Step 2: Connect learning priorities and questions to decision points.

The above outlines a curiosity and brainstorming exercise for the main event of discussing the types of strategic choices you will need to make in the future. For example, will you need to decide if you should be funding international or only local organizations? Will you be deciding where to work (countries or specific provinces within a country)? Will you need to decide whether an approach is proving useful and whether to continue funding it? Try and think through future decision points (this can be difficult for people, but is critical to having a useful learning plan).

Circle back to the questions the group brainstormed in Step 1. Do any of these questions help you reach conclusions on future decision points? If not, what questions should we be asking ourselves to be able to make informed decisions? Focus on the questions which are “need to know”. Questions that clearly don’t inform future decisions should be de-prioritized during Step 5.

Step 3: Understand what resources are available to implement the plan.

Get even more practical: ask yourself and your organization: what resources are available to support learning? This includes staff time (who will own and shepherd the creation and implementation of the learning plan on the team? Who on leadership will ensure that learning is infused into business decisions?). How much staff time is the organization willing to commit across the entire organization? What other types of resources will be allocated to support organizational learning? Asking these questions early on will help you right-size your organizational learning approach — from “organizational learning lite” to embedded, intentional, and systematic organizational learning practices on your team.

Step 4: Outline how learning will inform key business decisions on a specific timeline.

In this step, it is really important to think about the timing of decisions discussed during Step 2. In our experience, organizations can often be learning but not connecting that learning to decision-making points, especially decisions related to work planning. In this step, it is important to think about what you need to know and when. For example, if you know that you need to make a new work plan every July, how can you structure your learning activities in order to have the information you need in June so that you can make informed decisions? Another example would be if you host a quarterly training, what information would you need (and by when) in order to make informed decisions about that training design or delivery? Or, for activities that are rapidly happening, such as communications and engagement, how can you structure your learning activities to fit the pace and nature of decisions that your team would make in this area? For example, by creating a dashboard that has real-time information about indicators that are meaningful and important to that team?

To contribute to the sustainability of your learning efforts, it is very important to share with your staff openly how what has been learned informs ongoing decision-making. Show your team that you are doing something with those generated learnings and you will have enthusiastic participants for your next learning activity!

In this step, it is also important to consider the ways in which people learn. Experience and research show that people need to wrestle with information in order to make sense of it and actually learn. Or they need to learn by doing and get feedback. Either way, consider how you can structure opportunities for meaningful learning and do not make the mistake of thinking that if you simply share information with people that they will learn from it (let alone consider changing their behavior as a result!). Something we tried at USAID LEARN was playing games to help teams internalize data.

It is also important to consider the behavior changes that are necessary across the team to facilitate ongoing learning. For example, how can you incentivize and reward learning behaviors that happen in an ongoing way — outside of pre-programmed “learning moments” — across your team? It’s really more about a continuous mindset of learning to ask questions, being open to considering ways in which you may be wrong or make a false assumption, and being adaptive in your approaches on a daily basis.

Step 5: Outline who is involved in learning.

As mentioned elsewhere, learning is everyone’s job on your team, but you’ll need to fill some key roles to lead the learning process and ensure that learning gets integrated into business decisions. Be explicit about these roles to make sure that they actually happen. Those identified here should be involved in the rest of the process below.

Step 6: Identify learning priorities — these are often in the form of learning questions

In going through the strategy session(s), questions will naturally emerge about what you do not know related to your organization’s strategy and theory of change. It is important to source these questions widely across your team and to go through an intentional and transparent prioritization process. (For question inspiration, see this blog by Monalisa on learning questions everyone should be asking themselves, the learning questions checklist, tipsheet, and this webinar on asking powerful questions.) Developing a set of criteria to guide decision-making will provide a more objective lens through which to assess potential learning questions across the qualities the team deems most important. One criterion that is critically important is to ensure that the learning will occur on a timeline that is advantageous to the organization (can we learn enough to make a decision about this in a year?) and that it connects to the overarching strategy (if we know the answer to this question, how will that help us strengthen or adapt our strategy to achieve our goals?)

Something we’ve observed in this phase is that it is really easy to ask questions that have very little to do with the organization’s strategy and theory of change or that are unlikely to be used at the right time (or at all) to make decisions to strengthen or adapt the organization’s approaches. Be mindful of this creep that can happen and be very challenging and focused during this step.

Step 7: Identify learning activities.

In this step, it is important to start by identifying the ways in which you are already learning as an organization. As Dave Algoso shares, you are probably doing more learning than you think — it’s just happening in ad hoc or informal ways. Ask your team to reflect on what learning activities — whether those are After Action Reviews or making small changes to approaches based on indicator data — are working well, why, and how they can be applied in a systematic, intentional, and resourced way across the organization. It’s important to make sure that these learning activities are aligned with the learning questions or priorities you’ve established in step 2.

Next, consider other learning activities that could help you answer your learning questions that you are not already doing. Could you commission an evaluation? Could you collect data in the form of surveys or interviews? What would you need to do as a team to answer the questions you laid out?

Step 8: Establish a plan to revisit the learning plan and learn as you go.

Lastly, you will have to commit to continuous learning about how learning is going on your team. Establish a plan for revisiting the learning plan on a regular basis and reflect on what is working well, how you know (for example: what adaptations have you made in your approaches or strategy? How have those changes been informed by your learning?), and what you want to do to change.

Creating, implementing, and revisiting a learning plan is also a powerful way of modeling strong learning behaviors on your team. If you can do it in the creation and implementation of the learning plan itself, this could model for others how to approach their work overall. Heads up! It is completely normal to experience some ups and downs. Stay focused on using learning and demonstrating how an intentional approach to learning has resulted in tangible improvements and changes to how work is getting done.

Does this resonate with your professional experience? What have we missed? Connect with us at kat@gkinitiative.org or msalib@socialimpact.org so we can discuss more over a virtual coffee. Now that you know the steps we would recommend for creating a plan, read more about how to implement it and common challenges faced along the way!).